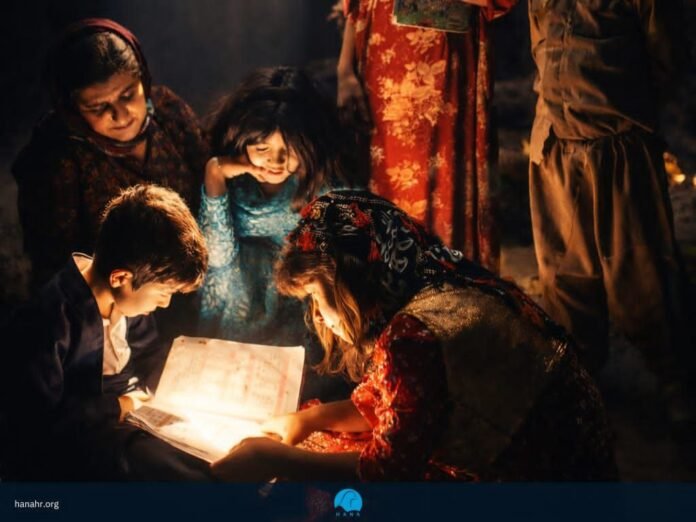

The right to one’s mother tongue is among the most fundamental human rights, particularly in an ethnically and linguistically diverse country. This right addresses how linguistic minorities can enjoy their rights in societies where no single language is shared by all, and it affirms that linguistic minorities must be able to use their own mother tongue—especially in education—rather than being forced to rely on the majority language.

The importance of the right to the mother tongue, and the principle of non-discrimination in its application, is explicitly recognized in international human rights instruments, including Article 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This right has also found clear expression in international jurisprudence. For example, the UN Human Rights Committee, as the body monitoring implementation of the ICCPR, ruled in a case brought by a citizen of Uzbekistan that education in one’s mother tongue constitutes a fundamental right essential to the preservation of a minority’s culture.

Education in the mother tongue not only safeguards the collective identity of linguistic minorities, but on an individual level it is a vital factor in academic advancement and in learning additional languages. This was explicitly emphasized in the report of the UN Special Rapporteur on minority issues published in March 2020. Systematic denial of this right, combined with an insistence on linguistic uniformity, leads to unequal access to social participation and pushes large segments of the population to the margins—particularly in a country such as Iran.

The Kurdish language, alongside other non-Persian languages in Iran, has consistently been a victim of policies of linguistic homogenization and denial since the very beginning of nation-state building and the emergence of the modern state. Under the leadership of the Islamic Republic, these dogmatic policies have intensified under the pretext of combating separatism. As a result, security institutions—exercising full control over key educational, cultural, and judicial policies—have never allowed the realization of the right to the mother tongue, even in the minimal form recognized under Article 15 of the Iranian Constitution. The systematic denial of the Kurdish language in the Islamic Republic has been accompanied by intimidation, fabricated security narratives, and harsh judicial sentences. Over the past year alone, several Kurdish language activists and teachers have been arbitrarily arrested by security bodies, deprived of their basic civil rights, and subsequently sentenced to long prison terms by Revolutionary Courts.

The Hana Human Rights Organization emphasizes that the right to education in one’s mother tongue is a fundamental human right and must be formally recognized in law, accompanied by effective and adequate guarantees for its implementation.